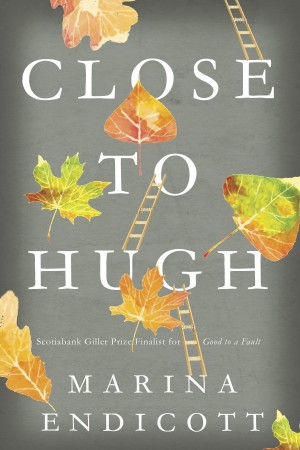

An exuberantly existential novel

about youth and age, art and life, love and death—

about losing your mind and finding your heart’s desire.

Amazon.ca McNally Robinson Chapters/Indigo

Late in October, a fall from a ladder leaves Hugh with a fractured vision of the pain suffered by all those close to him—dying parents, shaky marriages, failure of every kind. All his friends are one missed ladder-rung from going under emotionally, physically, and financially. Somebody’s going to have to fix them all, and it’s probably got to be Hugh. Meanwhile, beneath the adult orbit, younger troubles spin: the sons and daughters of Hugh’s friends are about to graduate from high school and already floating away from the gravitational pull of their parents. As complicated bonds form and break in texts and ticks on multiplying media, the desires, terrors, and revelations of adolescence are mirrored in the second adolescence of the adults. Close to Hugh revels in these two parallel worlds, in the puns and coincidences that attend every generation’s coming of age, or second coming.

Endicott’s ear for the cadences and concerns of two generations gives us two sets of friends on the cusp of reinvention. With exquisite insight and surefooted mastery, she manages something surprising: to show us, with an unerring ear for the different cadences and concerns of both generations, two sets of friends on the cusp of simultaneous reinvention. As always in Endicott’s multi-layered fiction, underpinning the sharp comedy and keenly-observed drama is something more profound: a rare and rich perspective on what it means to rise and fall and rise again, and what in the end we owe those we love.

“Delightful, tragic, gloriously elegiac and riddled with puns—Close to Hugh is just like life, only so much more beautiful for being art.” Lynn Coady, author of Hellgoing and The Antagonist

Globe & Mail

“Marina Endicott’s oddly original and charming new novel, Close to Hugh, inhabits a particular geography involving a series of staircases. The two flights up to Hugh Argylle’s mother’s hospice bed; the concrete stairs from his friend’s condo by the river; the claustrophobic staircase with doors at the top and bottom at the home of Hugh’s ex-wife who is also, inconveniently, landlady to his new flame; and the steps leading to Hugh’s small art gallery just below his apartment, which is up another flight. Then there is the ladder upon which Hugh is standing, hanging strings of lights, when he falls. Falling is as much a motif in the novel as stairs are. Fall as in the autumn season and one’s autumn years, and as in to plummet. Down, like the direction and like feathers, the thing with which is hope, according to Emily Dickinson… Close to Hugh is also about puns and anagrams—words so conspicuous in their materiality—Jung and Buddhism, show business, homophobia, grief and friendship, flooded basements and vintage fashion. Its prose is stream-of-consciousness, like the river that runs through Endicott’s imagined city (a fictionalized Peterborough, Ont.), “where water pours into water like the soul pours itself into the world, over and over, looking for home…” Rich with adjectives, the novel addresses huge and general questions about the meaning of life and the universe with remarkable specificity. “We are tiny, unknowable, unimaginably unimportant, far from everything, only close to each other,” one character observes, which on a macro level is the point of Close to Hugh but, as the novel demonstrates, is also totally wrong. Because of how art itself brings the world into startling, vivid focus, and suddenly every little thing has meaning after all.” Kerry Clare, Globe and Mail

Toronto Star

“Reading a new novel by Marina Endicott, I am often reminded of the work of the late Carol Shields, the casually understated depth of her talent. It’s not just that Endicott shares with the American-born, wholly Canadian Shields an impressive skill, a comfort in writing in whatever form or approach she chooses; she also shares with Shields a fundamental, deep-seated humanity… It’s a novel of connections and bonds, of community and relationships. And it’s not all dark: Close to Hugh is, at times, wildly funny, both broad and tightly focused. This humour, however, is somewhat misleading. While it has the feel of a comedy of manners (a sense amplified by the examination, within the book, of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest), and may put some readers in mind of Robertson Davies’ Tempest-Tost (the first novel of the Salterton trilogy), Close to Hugh cuts far deeper, peeling back pretensions and facades in pursuit of those fundamental human truths so dear to Endicott, and to Shields before her.” Robert J. Wiersema, Toronto Star

Literary Review of Canada

“The book’s voice… is alive with impish humour, a deep reservoir of humanity and a gift for quirky, evocative phrasing. These have always been strengths of this Edmonton-based writer’s work, even in her first novel, the straightforward first-person Open Arms, but in Close to Hugh, her fourth novel, she has taken things to another level: it is more droll, more insightful and even better crafted than its predecessors. Every sentence in this book made me want to read the next one. The wondrous thing is that Endicott employs this distinctive voice entirely in the service of her characters.” Jack Kirchhoff, Literary Review of Canada

Quill & Quire

The weight of what we carry with us while travelling through life, and the pain we suffer in doing so, is the foundation upon which Endicott structures her story… Close to Hugh could be said to encompass universal philosophical themes, but to Endicott, they are almost molecular, focusing on invidual lives and the potentially defeating moments in the day-to-day existence of a small group of people: “How we learn to bear the bad parts, how we figure out how things could be better. How we can live with others, how we can bear to live alone… People don’t understand each other and yet they keep working to, because they love each other.” (Laurie Grassi)

Follow @marinaendicott

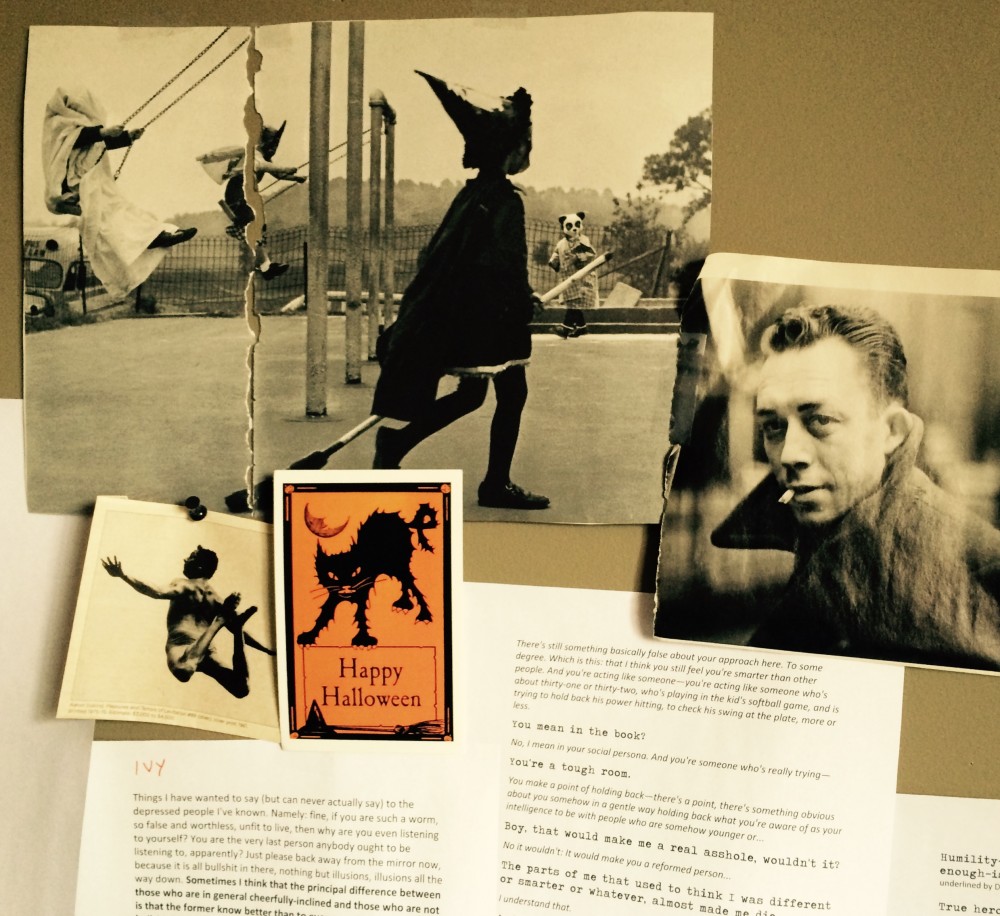

Hugh images on the writing wall