‘This is stage right,’ Joy said. But it was on the left, the side their dressing-room was on.

‘This is stage right,’ Joy said. But it was on the left, the side their dressing-room was on.

‘You have to think of it from onstage, not from as if you was watching.

It’s from our eyes they named the sides, because we’re the simple ones!’

The Little Shadows

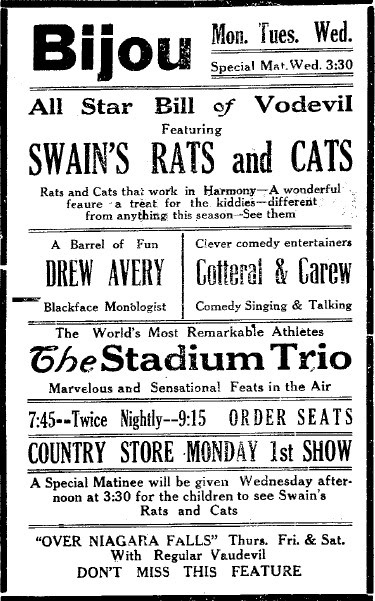

Music in The Little Shadows • Vaudeville sources • Vaudeville circuit map • Playbills • Behind the curtain

Ad lib — short for ad libitum (Latin) meaning at will; speeches or business made up on the spot.

All washed up — A performer was “all washed up” when he could no longer get a booking anywhere, when he had proven unreliable or just not very good.

Apron — The part of the stage projecting out past the proscenium.

Big Time — The big leagues of vaudeville. The best circuits offered first-rate programs with the best available performers including big-name stars. The two high class circuits were the Keith Circuit in the east, and the Orpheum Circuit in the West. This was the big time. These two circuits were also known as the ‘two-a-day,’ because of their policy of presenting only two performances daily, matinee and evening. Small time venues were the theaters in small towns across the country, or the cheaper houses in large towns (sometimes even crude storefronts with benches for seating). Small time was the training ground where new performers created and polished their material for three or more shows a day, and worn-out performers worked a last few years. Vaudeville circuits were invariably referred to as ‘time.’ Thus, instead of the Pantages Circuit a performer would say: ‘I’m going to play Pan time.’ Performers called the better class circuits ‘medium time’ to distinguish them from the cheap low-grade theatres in which inferior acts worked at a miserable salary.

Bill — The playbill, the program or list of acts, in order of performance.

Billing — The names of performers as displayed on a theater’s marquee and in its advertising. Status determined order on the list or gave billing in larger type.

Bit — A sketch, routine, trick, any segment of an act.

Blue material — Sexual or toilet references or profanity. E.F. Albee, king of the massive Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit, insisted that performers stick to strict standards of propriety. Sophie Tucker, in her biography Some of These Days, wrote “Between the (Monday) matinee and the night show the blue envelopes began to appear in the performers mailboxes backstage … Inside would be a curt order to cut out a line of a song, or piece of business. … There was no arguing about the orders in the blue envelopes. They were final. You obeyed them or quit. And if you quit, you got a black mark against your name in the head office and you didn’t work on the Keith Circuit anymore.” The tint of those envelopes gave “blue material” its name.

Boards — The stage. Theater stages are surfaced with rows of wooden boards, made of soft wood and replaceable when too worn, that allow scenery to be nailed or screwed down temporarily with special screws topped with wings for easy insertion and removal by hand. To “hit the boards” was to take up a career in the theater, or for a show to move from rehearsal to performance. To “tread the boards” is to have a stage career.

Border — The short immovable drop at the top of each cross-stage curtain, masking the above-stage equipment when the curtain is open.

Border lights — The crudest type of general stage illumination. A metal box the width of the stage, hung just behind each border, containing a row of electric lamps – each lamp covered with a glass color filter, alternating red, blue and green. The lighting board could only control the intensity of each general color group.

Breaking in an act — Playing an act before an audience until it runs smoothly.

Bundle act/Suitcase act — An act that did not require trunks or crates full of props, costumes or rigging, since vaudeville performers were independent contractors responsible for the expense of carting everything their act required (including specialized scenery in the case of “flash acts” [q.v.]). Modern magicians call the principle “packs small, plays big.”

Call — The time a performer is expected to be at the theater. “I have a 5pm call.”

Catch-phrase — A common phrase said in a extraordinary manner which becomes the trademark of a particular comedian, as in Steve Martin’s “Excuuuuuuse me!” Vaudeville audiences were more familiar with Joe Penner’s “Wanna buy a duck?”

Chasers — Performers playing last on the bill, named as if they were so bad they chased audience stragglers out. William Dean Howells, writing in Harper’s Monthly in 1903, wrote “Very often they are as good as the others, and sometimes, when I have determined to get my five hours’ enjoyment to the last moment before six o’clock, I have had my reward in something unexpectedly delightful in the work of the Chasers, I and the half-dozen brave spirits who have stuck it out with me, while the ushers went impatiently about, clacking the seats back, and picking up the programs and lost articles.”

Circuit — A multi-city chain of theaters joined by the same ownership and booked as a block.

Close — To perform the last act after a star’s performance (“I closed for Jolson in Peoria”).

Cold — A “cold” audience is in a bad mood and shows it by responding poorly to even the best entertainment. A performer may be thrust onstage suddenly by circumstance (perhaps the next act just keeled over of a heart attack) and have to perform “cold” .

Counting the house — Looking out into the house surreptitiously, to estimate the box office success of the show.

Crossover — A stock comedy routine, easy to put together because it needed no involved setup. Two performers enter from opposite sides of the stage, meet in the middle for a bit of comic dialogue, then each exits in the direction he was going. For instance, one guy has a suitcase … “Where are you going?” “I’m taking my case to court.” (They meet again, the guy now has a ladder.) “Where are you going now?” “I’m taking my case to a higher court.”

Death Trail — Different circuits were characterized according to their most notable qualities. The “Death Trail” was the early name for a string of small, cheap theaters in the west.

Deuce Spot — Second act on the bill. Considered to be the worst spot in the program (the usual opening “dumb act” not even being worthy of consideration by a self-respecting artiste.) The second spot was forgettably early in the show when the audience had not yet been warmed up to a good level of response, and just before the big star whose act would eclipse whoever played the deuce spot.

Dialect Act — An act (usually comedy) using dialect material (a broad accent and ethnic humor: German, Italian, Jewish, Irish or black). This brand of humor went over well in a time when most of the audience had just gotten off the boat from somewhere else. They accepted humor directed at any immigrants as humor related to their own experience, especially when immigrants tended to be embarrassed by their “simple” origins and yearned to become more American.

Died — Played to perfunctory applause or none at all.

Drop — Lateral curtains extending the full width and height of the stage are called “drops.” They may be hung at various distances from the footlights (see “olio”). They might be simply draperies, or they might be painted with various scenes and serve as simple sets. A good theater would have a variety of painted drops representing generic settings, like “garden drop,” a “palace drop,” a “woods drop,” a “street drop,” coordinating with stock furniture and set pieces (a garden bench, a throne, a tree stump, a street lamp). The very front curtain was usually called the “house drop.” The “street drop” usually hung just behind the house drop for simple “two guys meet on the street” routines played close to the footlights.

Dumb act (or Sight act) — An act that did not involve speech, usually performed to music, such as an acrobatic act or a juggler. A dumb act was often first and/or last on the bill because the audience was still entering (or leaving) noisily.

Dumb Dora — slang for a comically mindless female. The name was applied to a standard two-person vaudeville act in which the man (playing ‘straight’) would try to communicate with the woman, whose odd logic defeated all attempts to make sense. George Burns and Gracie Allen elevated this scenario to its highest form (see “Straight Man” below). The precursor of “dumb blonde” humor.

Excess baggage — A vaudevillian’s spouse, if he or she tours with the performer but does not perform.

Finish — The finale of an act, especially when it contrasts with the rest of the act (the performers in a comedy act might break into a song and dance, or finish with a pie in the face or some other effect.)

Fire curtain — A fireproof curtain of asbestos fabric, set immediately behind the proscenium arch, almost touching it and traveling in metal guide channels (‘smoke pockets’) so as to cover the opening fairly tightly. It could be lowered when the theater was dark and raised a few minutes before the show, and was also rigged to drop quickly at the pull of a stage-side handle in case of fire (a theater, including the house, stage and fly gallery full of combustibles, is a huge and very efficient fireplace). Most building codes required a fire curtain and automatic fireproof stage doors in theaters with a stage height of more than 50 feet.

Five — “The five” is the stage manager’s warning that ‘places’ will be called in 5 minutes.

Flirtation act — An act (sometimes comic) based on flirtatious banter between a man and a woman, and perhaps a romantic song and dance.

Fly gallery (or “the Flies”) — The area above the stage, ideally an additional 1½ times the height of the proscenium arch, where a system of ropes and counterweights allows lights, drops and other pieces of scenery to be lowered to the stage.

Footlights — A row of lights at floor level extending the width of the front edge of the stage. Used in the days of gaslight (or inefficient electric lighting) to illuminate performers working very close to the front.

Gallery — The balcony. Gallery seats were the cheapest.

Get back your pictures — To be cancelled or fired (your promo photos were removed from the lobby displays and returned to you).

Ghost light — A single bare bulb on a head-high stand, left lit on the stage overnight for safety.

Glass-crash — A basket filled with broken glass, used to imitate the noise of breaking a window and the like.

Go big — When a performer, act, song, gag, etc., wins much applause it is said to “go big.”

Grouch Bag — A small bag or purse worn under the clothing, carrying the performer’s valuables (which are likely to be stolen from an unattended dressing room).

Half-hour — The first of several calls (backstage announcements to performers in their dressing rooms or the green room) by the stage manager, culminating in “places” at showtime. All performers were required to sign in by half-hour or face penalties. Also called “the half”: “I have to be at the theater by the half.” Half-hour is usually called at 35 minutes before curtain (30 minutes to the “places” call), quarter is called at 20 minutes, and the five is called at 10 minutes before the show begins.

Headliner — Star of the show whose named appeared most prominently on the bill and in the advertising, perhaps even “name above the title.”

Hemp — Scenery and lights were originally hung from pipes suspended by hemp ropes. Each set of lines was rigged to be raised into the fly gallery above the stage or lowered into view, and tied off at the pin rail. Steel wire and counterweights replaced ropes hauled by simple strength, but some theaters did not upgrade and were known as “hemp houses,” connoting that the owners may have decided not to modernize other parts of their facility either.

Hoofer — Dancer.

Horse — see Stooge, a confederate who allows the illusion of performing miraculous effects on a randomly-chosen audience member. Unremarkable looking, and poorly paid.

House — The audience seating area. When the doors are opened to admit the audience, it is said that “the house is open,” and it would be very unprofessional for a performer to be seen in that area (unless performing as a stooge). May refer to the theater as a whole: “The Orpheum is a high-class house,” or “I don’t bring my own, I just use the house scenery.”

In One — An act or routine that works in the six-foot area between the footlights and the closed main show (number one) curtain. An act that needed that area plus the next six feet was “in two” since that area was in front of the number two curtain, and so on up to “full stage.” While various theaters’ stage dimensions might vary a bit, these specifications were standard ways of describing an act’s space requirements, and were a primary consideration in planning the practical flow of a full program.

Intermission — Between the two halves of a vaudeville show, a chance for the audience to buy refreshments; also a joking name for a performer so dull that he might as well not be onstage: “He was a long intermission.”

Ingenue — An actress playing, or a role depicting, a young woman.

Juvenile — An adolescent performer, or a role depicting a youth.

Kill — To be a wild success with the audience. “You’ll kill at the Palace!”

Knockabout — Exaggerated physical comedy like pratfalls and mock violence (the Knockabout Ninepins, for example).

Leg — A narrow drop beside each cross-stage curtain, masking the wings from the audience’s view. Legs are in pairs, stage right and left.

Legitimate theater — Or just the Legitimate; the term differentiates serious drama from mere entertainments like vaudeville or burlesque.

Limelight — An early pre-electric stage light, using a hydrogen/oxygen flame to heat a cylinder of lime, raising it to white-hot incandescence. The term is still used to mean “being in the public eye”.

Monologist — A performer whose one-person act consists entirely of talk. Probably the origin of modern “stand-up comedy,” the vaudeville monologist’s act might also be serious (a patriotic or poetic recitation), and the material might be rendered straight or in dialect.

Olio — In every vaudeville theatre there is an Olio painted backdrop and, although the scene which it is designed to represent may be different in each house, the street Olio is common enough to be counted as universally used. Usually there are two drops in One, either of which may be the Olio, and one of them is likely to represent a street, while the other is pretty sure to be a palace scene.

Olio Acts — Smaller numbers or acts performed “in one” during set changes for the major acts of the show. ‘Olio’ derives from ‘oilcloth,’ meaning cloth treated with oil or paint. The “olio drop,” often painted with advertising for local businesses, hung 6 to 10 feet back from the footlights. Simple specialty acts would perform in front of the “olio drop” while the stage was being set for the next major act. Such acts might be called for with ads such as: “Wanted: Acrobatic, juggling, and other novelty acts, to work in olio.”

One-Liner — A joke made up of only one or two sentences.

Open — To give the first performance of a show (“the show opened Saturday in Boston”), or to perform the warmup act before a star’s performance (“I opened for Sarah Bernhardt in Boston”).

The Palace — the apex of vaudevillians’ ambition, the finest vaude house in New York. (“Don’t tell me how you killed at the Palace, do it here!”)

Paper — Complimentary tickets given out (“papering the house”) to give the impression that the show is drawing large crowds. Often done on opening night when critics were in attendance.

Patter Act — An act based on rapid, clever dialog (Abbott and Costello’s famed “Who’s On First?” is an example.)

Pit — The sunken area immediately between the edge of the stage and the first row of the house, in which the house musicians play.

Playing to the haircuts — Playing last on the bill (in other words, playing to the backs of the audience members as they left.) In its worst construction, performing so badly that the audience walked out in boredom and disgust.

Point — the apex of the joke, the punch-line. “Get the point” is now in common usage.

Prop — Short for “property”, any item onstage other than scenery.

Protean Act — A quick-change act (from Proteus, a Greek god who could change shape).

Quick Change Act — An act in which a performer entertains by lightning-fast onstage costume changes.

Roper — A cowboy act.

Running Gag — A joke or physical bit which appears several times throughout the show, gaining momentum each time through its familiarity and through its appearance in a new context.

Set Diagram — Part of the technical requirements package sent on to theatres ahead of the performers, showing the layout of the act onstage, with a list of required props and lighting cues. Sometimes very elaborately drafted plans, sometimes a sketch drawn on a scrap of paper. Higher-paid acts had their technical requirements professionally printed; the medium-time could not afford the expense, and copied their plans by hand.

Sight Gag — A joke which conveys its humor visually.

Sidewalk Comedy — Comic act in front of the olio, the setting often being “two guys meet on a sidewalk.”

Single — An act by a single performer.

Sister act — Any vaudeville act with women singers, not necessarily related. Sometimes comic, sometimes straight.

Sitting on their hands — An audience resolutely refusing to applaud.

Slapstick — Knockabout physical comedy, named for the “slapstick,” a bat-like paddle with a flap that emits a huge “slap” sound when struck.

Sleeper jump — An overnight railway trip to the next booking—but also the top-floor dressing room, assigned to lesser acts. The higher an act’s status, the closer to the stage their dressing room. Old theaters had dressing rooms stacked all the way to the fly loft (four or five storeys), reached by iron backstage stairs all the way up. The top dressing room was the farthest, the hottest, the least-well maintained, and performers had to carry their wardrobe trunk up all of those narrow flights. Called a “sleeper jump” because it was so far from the stage that it took an overnight railway trip to get up there.

Small Time — Anything but Keith’s, in some vaudevillians’ opinion. Circuits playing more than two shows a day.

Sound-Effects — all vaudeville theatres have glass crashes, wood crashes, slap-sticks, thunder sheets, cocoanut shells for horses’ hoof-beats, and revolvers to be fired off-stage, they could not be expected to supply such little-called-for effects as realistic battle sounds, volcanic eruptions, and like effects. If an act depends on illusions for its appeal, it will, of course, be well supplied with the machinery to produce the required sounds. And those that do not depend on exactness of illusion can usually secure the effects required by calling on the drummer with his very effective box-of-tricks to help out the property-man.

Special light-effects — stage illumination to create practically any effect of nature. “If the producer wishes to show the water rippling on the river drop there is a “ripple-lamp” at his command, a clock-actuated mechanism that slowly revolves a ripple glass in front of a “spot-lamp” and casts a realistic effect of water rippling in the moonlight. By these mechanical means the moon or the sun can be made to shine through a drop and give the effect of rising or of setting, volcanos can be made to pour forth blazing lava and a hundred other amazing effects can be obtained. In fact, the modern vaudeville stage is honeycombed with trapdoors and overhung with arching light-bridges, through which and from which all manner of lights can be thrown upon the stage, either to illuminate the faces of the actors with striking effect, or to cast strange and beautiful effects upon the scenery. Indeed, there is nothing to be seen in nature that the electrician cannot reproduce upon the stage with marvellous fidelity and pleasing effect.” (Brett Page)

Split Week — in which an act was not booked for a full week in one theater but played part of the week in another house (or spent the rest of the week in travel to the next theater).

Stage Door — The entrance from the street to backstage. A bulletin board located here holds a daily sign-in sheet, information about nearby hotels and restaurants for the benefit of traveling artists, and rules particular to that theater. There might also be a set of mailboxes for the performers to receive mail or notes from the producer (see “blue material”).

Stage Left — The side of the stage that is on the performer’s left as he faces the audience (“stage right” is the other side).

Stage Manager — The real, day-to-day boss and hero of show business. He or she sits on a stool at a podium just offstage to the left of the performers (stage left), issuing orders as the show proceeds. The stage manager calls lighting and scenery cues, and in the case of revues he may even supervise rehearsals after the director has gone off to direct some other show.

Stooge — A comic aide to a comedian, often a performer who appears to a “volunteer” called up to help from out of the audience.

Straight Man — Half a comic team, the performer in a routine who plays the average Joe, the person the audience can identify with, who converses with someone odd or oblivious. George Burns was the straight man in tandem with wife Gracie Allen. He said, “I just stand there and ask Gracie questions, she answers in her way, the audience applauds and thinks I’m a great comedian.”

Suitcasing — Travelling on tour with very light or minimal baggage. Performers paid their own expenses between engagements, including the expense of shipping the props and scenery their act required.

Tag Line — An additional punch line to a joke; gives a second laugh without a new setup.

Take — A comedic facial reaction. A double-take is a take: noticing something, starting to move on, followed by a quick return to the sight and a surprised reaction to what you’ve just seen. A spit take is a reaction of such shock that the performer sprays out whatever he had been drinking or eating when the stimulus was received.

Teaser — The short drop just behind the proscenium arch, adjusting the visual height of the stage.

Terp Team — Ballroom or other paired dancers, from “Terpsichore,” the Greek muse of dance.

Tormenters — The legs (q.v.) just behind the proscenium arch, adjusting the visual width of the stage.

Trap — An opening in the stage floor enabling performers to go down, fitted with a secure covering to make the area just another part of the stage floor when not in use.

Two-a-day — Stage argot for vaudeville.

Upstage — Stages were often “raked” or slanted, higher in the back than in the front. Anything done upstage would be behind the back of the star, who would be downstage, facing the audience, and a misbehaving cast member could easily steal attention from the performer who should be the focus of attention.

Wings — The darkened areas offstage right and left, out of sight of the audience but clearly visible to performers onstage.

Wood-crash — An appliance so constructed that when the handle is turned a noise like a man falling downstairs, or the crash of a fight, is produced.

Work Lights — General utility illumination for the stage during non-performance times. Work lights for the house were called “cleaners.”

Wowed the Audience — Was a huge success, synonymous with a dozen other expressions like “laid ’em in the aisles,” “knocked ’em dead,” etc.

very freely adapted from several sources, including Brett Page’s Writing for Vaudeville and Vaudeville Lingo compiled by Wayne Keyser